Both the government and the average consumer are being forced to deal with debt more than ever before. But is there a healthier way to deal with spending?

Mat Megans, CEO at Hyperjar, examines current patterns of debt and spending and discusses how the status quo might be changed.

COVID-19 has impacted everyone in different ways. On an economic level, it was the tipping point that burst the bubble of expansion that started after the Great Recession ended in 2009. Now we are in a new recession caused by deliberate, but necessary, actions to try and prevent the rapid spread of the virus. Actions which have hammered the economy. Central banks around the world had to drop interest rates, often to as close to zero as makes no odds, to try and stimulate demand. The average UK consumer is facing this grim situation whilst sitting on a pile of debt even larger than the previous peak in 2008.

So, what about The Great Recession?

The Great Recession was a crisis of our own making that almost took down the global financial system. It caused such a scare that governments around the world implemented various regulations to try and prevent a repeat ever happening again. In the UK, one such regulation was ring-fencing, the set of rules that apply only to UK banks with more than £25 billion of core deposits. The main objective is to separate essential banking services from riskier lending activities – to try and avoid key banks dabbling in esoteric products like CDO-squareds and sub-prime mortgage securitisations. These indirectly led to people lining up in the street outside Northern Rock asking for their deposits back. Ring-fencing has definitely succeeded in making these deposits safer, but has also made it more difficult for many banks to earn attractive returns on capital.

This creates two side effects:

- There is less desire for aggregation of consumer deposits by many large banks;

- The big banks have increased levels of unsecured consumer lending compared to less profitable secured products such as mortgages.

Ring-fencing has definitely succeeded in making these deposits safer, but has also made it more difficult for many banks to earn attractive returns on capital.

What does this mean for the UK consumer?

I believe these conditions contribute to a number of trends seen over the past decade. Unsecured consumer debt has risen to all-time highs. Consumers are bombarded with offers for credit to buy almost anything, in almost every way imaginable – on social media, at the checkout till or online basket, in the post, at the ATM, on television. Fintech has also participated in driving innovation to make accessing credit easier and more prevalent with a strong increase in Buy Now Pay Later services at checkout.

The net result of this mountain of unsecured debt? Many people find themselves in very difficult situations as the expansion ends and recession sets in, leading to higher unemployment and increased personal financial difficulty.

Good debt and bad debt

Yes, we have a heavily indebted consumer. But debt isn’t always bad. In fact, some debt is a tool that creates significant happiness and wealth, for example: mortgages. A small deposit can help buy a house, and even modest levels of price appreciation over the long term can net attractive returns, or allow for mortgage repayments which are lower than the rent for an equivalent property. I call this good debt, debt used to generate positive returns and outcomes. Then you have other forms of good debt which arise through unplanned necessity, for example debt used to buy a car that’s essential for work, or a broken boiler that needs to be repaired.

Bad debt is none of this. It’s debt used to buy depreciating assets such as a nice pair of shoes or the latest gadgets that do not generate real, absolute or relative financial returns. Problems can often arise as bad debt accumulates, sometimes on top of necessary good debt. What inevitably happens is those with the smallest financial buffer have the worst debt, and this means they suffer more in a recession.

What can we do?

It’s not all dark and gloomy. We can do a lot. It has become a cliché, but in this case, we really can build back better, and not just as a political slogan. Perhaps we can rewire society’s relationship with spending and debt:

- Lockdown has made many appreciate the simple things in life. A ‘gratitude attitude’. Time with family, friends, relationships and nature are increasingly valued personal ambitions – maybe this may make us a little less susceptible to buying material objects for instant gratification, and a little more cautious about taking on debt to buy things that we cannot really afford.

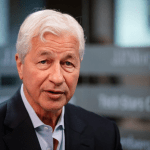

- Economic uncertainty has led many people, who have the ability to do so, paying down debt and increasing savings at unprecedented rates. To play on the infamous words of ex-Citibank CEO Chuck Prince, many people recognise the music has stopped playing and it’s time to stop dancing. They’re building buffers.

- A younger generation is growing up and joining the workforce in extremely difficult times and they have different attitudes to debt and excess conspicuous consumption. Sustainability is one of their driving forces and this applies not just to carbon footprint but also to their finances.

- Near 0% interest rates on current and savings accounts is becoming front page news and a topic people are thinking about and discussing. It offers the opportunity for other stakeholders besides banks to step in and help give savers attractive options. The topic of financial literacy is becoming more prominent and there now exist many popular Instagram influencers who talk about personal finance. Being responsible with your money is becoming cool.

[ymal]

These factors set up an opportunity to reset and to think about fintech business models which are designed around savings, not around debt. At HyperJar we are working with a group of forward-thinking retailers to offer attractive rewards to consumers who can commit funds that will be spent with them in the future. The funds are safely held at the Bank of England until our customers are ready to spend it. On top of the rewards, which grow dynamically over time when money is allocated, you’re less tempted to spend on things you don’t need. A win-win between shoppers and the places where they shop. That’s a future we think is possible and worth trying to build.