From the original Ponzi scheme to the largest of all time, we take a deep dive into the cunning workings of 3 of the world’s most famous fraudsters.

What Is A Ponzi Scheme?

Named after the Italian con artist Charles Ponzi, a Ponzi scheme is an investment fraud where existing investors are paid with funds from new investors. Typically, the orchestrator of a Ponzi scheme will promise to invest a person’s funds to generate higher returns with little or no risk, similar to, though not to be confused with, a pyramid scheme. However, some fraudsters don’t invest the money at all. It's important to take precautions and stay updated on fraud management trends to protect yourself and your organization from scams. Today, new technology offers better ways to detect and prevent fraud, like machine learning algorithms that can spot unusual patterns in financial transactions.

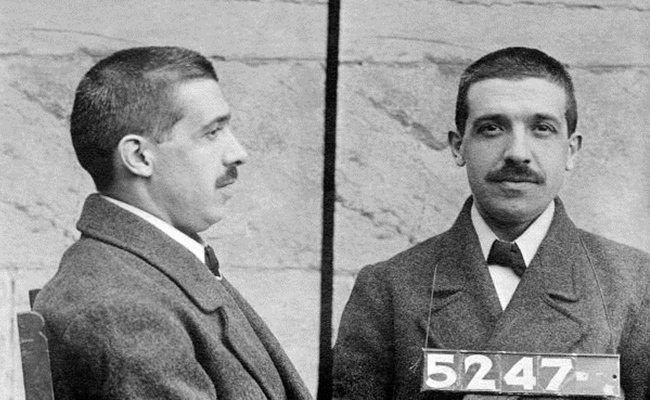

1. Charles Ponzi

Although the term “Ponzi scheme” took its name from fraudster Italian Charles Ponzi, the first recorded instances of this type of investment scam can be traced as far back as the mid-1880s, carried out by the likes of Adele Spitzeder in Germany and Sarah Howe in the United States.

Nonetheless, Charles Ponzi is widely thought of as the “original Ponzi scheme”. His scam centred on the postal service, at a time when it had developed international reply coupons (IRC) which allowed a person in one country to pay for the postage of a reply to a correspondent in another country. An IRC was priced at the cost of postage in the country of purchase, though could be swapped out for stamps to cover the cost of postage in the country where it was redeemed. A difference in these values would lead to a potential profit and, due to post-Great War inflation, an IRC could be bought cheaply in Italy and exchanged for US stamps of notably higher value. These stamps could then be sold on. Ponzi claimed that the net profit of these transactions worked out at over 400% — a form of arbitrage that was completely legal.

Realising the huge potential of his scheme, Ponzi left his job and committed to setting his IRC plan in motion. However, upon seeking funding, several banks rejected his application. This led Ponzi to establish a stock company to generate funds from the public, as well as to turn to several of his Boston friends. He promised to double their investment in 90 days, a promise which he later shortened to 45 days at 50% interest.

At the end of 1919, Ponzi founded the Securities Exchange Company in Massachusetts to promote his IRC scheme. Within a month, 18 investors put a total of $1,800 into his company. The investors were paid the next month, with money Ponzi secured from his next set of investors. Over time, Ponzi’s business expanded and he began to hire agents to seek out new investors across New England and New Jersey.

Ironically, three-quarters of Boston’s police officers were said to have invested in Ponzi’s scheme. Meanwhile, a banker from Kansas put down $10,000. In late July 1920, Ponzi raked in an impressive $1 million in a single day and, according to Smithsonian Magazine, he generated an estimated $15 million in eight months. While this figure may seem small compared with larger modern-day scams, what’s particularly impressive about Charles Ponzi’s scheme is the sheer speed with which he made his millions.

2. Bernard Madoff

Bernard Madoff, or “Bernie Madoff”, was an American financier who executed the largest Ponzi scheme in history. Thousands of investors were defrauded out of approximately $64.8 billion over the course of at least 17 years by Madoff, who died in prison in April 2021 while serving a 150-year sentence for money laundering, securities fraud, and several other felonies.

In 1960, Madoff established his firm Bernard L Madoff Investment Securities, which soon enough became one of the largest market makers and was investigated on eight occasions by the US Securities and Exchange Commission over its exceptional returns. However, it was the global recession of 2008 that led to Madoff’s demise when investors tried to withdraw approximately $7 billion from his funds. It soon became clear that this was a figure Madoff did not have.

Those defrauded by Madoff included actor Kevin Bacon, film director Steven Spielberg’s charitable foundation Wunderkinder, and professional baseball player Sandy Koufax. Banks were also affected, including HSBC Holdings, Royal Bank of Scotland, and Japan’s Nomura Holdings. Ordinary people were also victims of Madoff’s fraud.

In court, Madoff said that when he began the scheme in the 1990s, he had only planned to continue it for a limited period. He pleaded guilty in March 2009, saying: “I am painfully aware that I have deeply hurt many, many people, including the members of my family, my closest friends, business associates and the thousands of clients who gave me their money. I cannot adequately express how sorry I am for what I have done.”

3. Lou Pearlman

Lou Pearlman was an American record producer, who was at his height of fame in the 1990s after launching two of the most popular boy bands, the Backstreet Boys and NSYNC. However, what the public failed to realise at the time was that Pearlman had also launched a Ponzi scheme. For around two decades, Pearlman would convince banks and everyday people to invest in companies that were entirely fabricated.

After NSYNC and the Backstreet Boys proved to be global success stories, investors quickly became keen to share in the wealth the American producer had created for himself. This opened up an all too easy opportunity for Pearlman. He began working as a con artist, encouraging keen investors to buy into Trans Continental Airlines Travel Services Inc and Trans Continental Airlines Inc — two entirely fabricated companies that existed only on paper.

It wasn’t until 2007 that Pearlman finally came under investigation. Originally, he told Florida state officials that the money was invested into a company called “Germany Savings”. However, unable to locate the company, Florida state officials began searching for the accounting firm that handled Pearlman’s financial statements. Officials traced the records to two separate addresses — one in South Florida, where no such firm appeared to exist, and the one that shared the same address as “German Savings”. It was revealed that this second address was linked to a remote answering service, paid for by investors.

Having swindled $300 million from banks and investors, Pearlman pleaded guilty in 2008, charged with conspiracy, money laundering, and false bankruptcy proceedings. He was given 25 years in prison but died in federal custody in 2016.