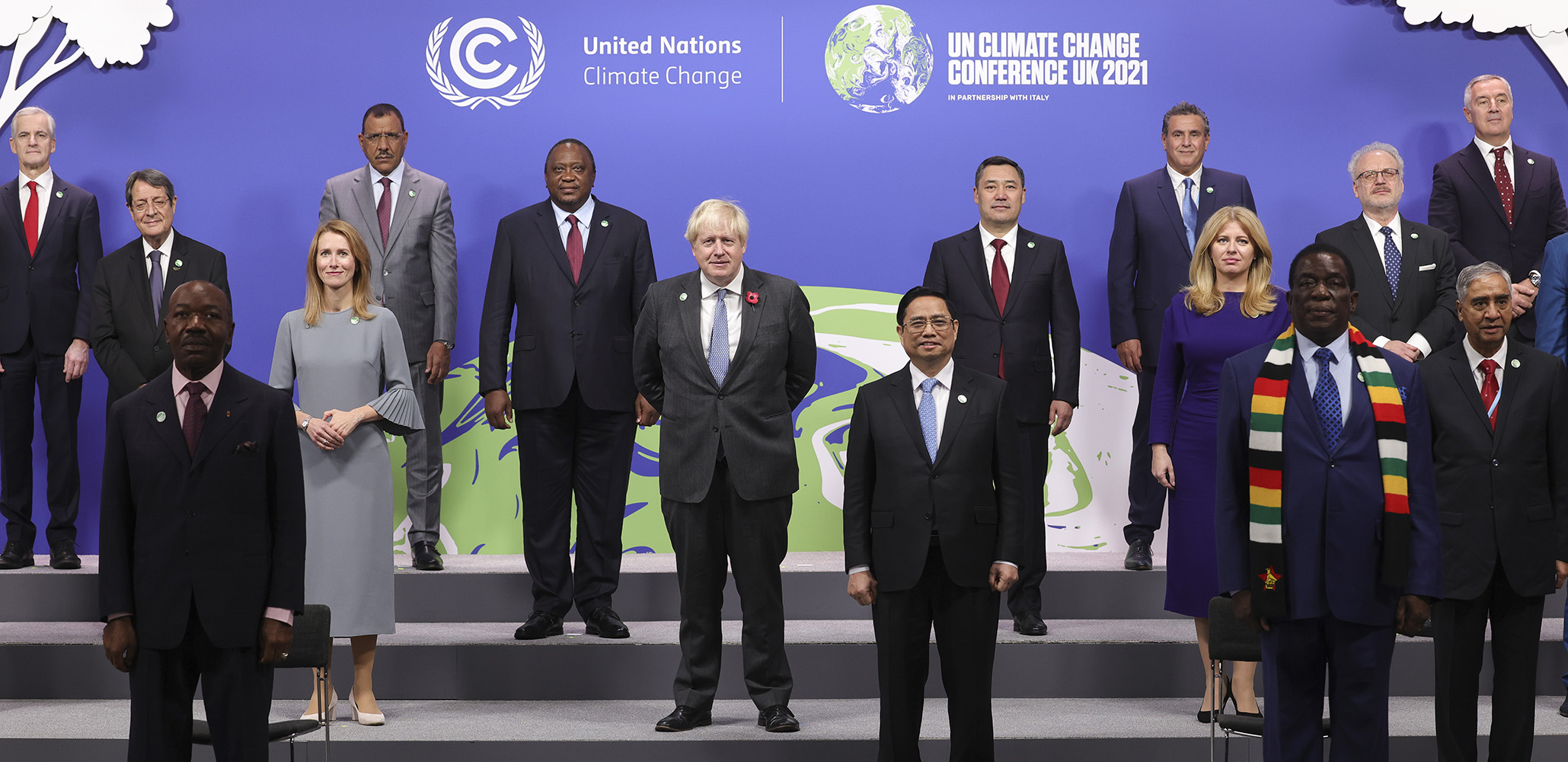

The international conference Sherpas who ran the COP26 climate change conference are no doubt relieved with the little steps towards a post-carbon economy the 10-day Glasgow gab-fest achieved. The pledges fell short of the most optimistic hopes, but little steps forward are better than walking backwards.

The wheels of global agreement move slowly – since the first Berlin COP1 in 1995, global CO₂ levels have risen nearly 50%, temperatures are up 0.5 degrees, and the ice on the Greenland cap is melting faster than ever. Around the world, governments are increasingly alert to the reality. The amount of CO₂ in the atmosphere has risen historically faster than ever before, and rising CO₂ levels presage higher temperatures. Even the Saudis get the cause and effect and say they will redirect their economy towards carbon neutrality by 2060.

The problem is large conferences inevitably result in compromise. Compromises beget consequences. Various themes that have emerged from the conference will all impact society and markets in the coming years. These include:

First: the trajectory of carbon pledges and mitigation plans still mean global emissions will continue to rise before tailing off later this century. The experts believe this effectively means political promises to keep temperature rises to a mildly uncomfortable 1.5 degrees look increasingly impossible to keep. The scientists reckon 2.4-2.7 degrees by the end of this century is more likely, and even that depends on everyone sticking to promises.

Second: rising temperatures mean higher costs and more chaotic weather events – like the floods, fires, storms and ultra-high temperatures we’ve seen this year. Mountains are becoming less stable as the ice-binding them literally melts. Increasing climate instability will raise political protests. The consequences will fall heaviest on the poorest nations, meaning the requirement of increasing financial transfers to help them, which leads to.

Third: the problem of how to support and compensate less developed nations has become an urgent matter. Funding to ameliorate climate change and transition from fossil fuels has already fallen well short of what was promised at the Paris COP. While $100 billion is on offer, that’s the same sum India wants as a precondition to action its promised zero-carbon plan for 2070! And, sadly, there is growing suspicion many countries and corporates will try to free-ride CO₂ emission cuts by others, setting up for rising geopolitical tensions.

Fourth: is the critical issue of Energy transition. It sometimes feels like there is an assumption we can just turn every fossil energy source off, and immediately replace them with renewable power – but that’s clearly impossible, unless, of course, you want to switch off the whole global economy.

A well-considered energy transition plan is critical but it’s not simple. Thus far the approach has been to encourage renewables through subsidy and market pressure, primarily the E for Environment in ESG investing – which is becoming increasingly fundamentalist in its application – refusing to countenance any fossil fuel investments.

But market pressure to end investment in fossil fuels and transfer it into renewable is fraught with difficulties. Every investor on the planet now wants to finance and buy renewable power assets, but that means they finance the simple, easy and swiftest returns; like solar and wind power. These are proven and now produced in such numbers the costs of Wind and Solar power have tumbled.

One of the reasons gas prices across Europe have spiked is because the weather in October was calm. As energy demand rose for the autumn, the wind farms came up empty. The reality is wind and solar are easy, but hopelessly inefficient sources of energy compared to more expensive renewable power sources. Hydro and tidal power are far more reliable but currently cost more. That cost will only fall if they see wider adoption.

This leads to the fifth problem – fooling ourselves. The reality is lifetime carbon savings from wind, electric cars, and other “feel-good” solutions are discounted in the effort to be seen doing something. Ultimately, to really cut the carbon load in the economy we probably need a Manhattan Project magnitude effort to innovate new energy-dense technologies in terms of capacitance (batteries) and nuclear power – eventually leading to fusion. Unlimited fusion could solve all our issues – but that’s what we said back in the 1950s after the first hydrogen bombs!

Pragmatists understand a complete restructuring of global energy provision can’t happen overnight. It took 200 years for the world to industrialise and destabilise the climate. With the right political push and incentives, we have the wit and wisdom, and innovative capacity to make it cleaner over the next 30-50 years. We are an inventive species, and we may actually succeed in making things better. Just not overnight.

There is a sixth danger from COVID, and that’s political. Look to the increasing impact of climate protests. COP was never going to be the magic wand climate protestors demand. If the numbers continue to move against neutrality, there are the consequences of green politics to consider.

Being green is no longer eccentric – it’s mainstream. Everyone will answer yes if asked about a better environment. That has moved the goalposts. Increasingly, extreme climate protestors are supporting “De-Growth” strategies – that it’s better to somehow switch off the world to avoid a catastrophic Malthusian disaster caused by too many people consuming too many resources and polluting our closed system spaceship earth. Malthus was wrong in the 18th century and is no doubt still wrong today!

Being green is no longer eccentric – it’s mainstream.

What COP26 protests and things like Insulate UK highlight is the potential for polarised green politics to collide with the economy and growth. It’s going to take years to wean the economy off fossil fuels, but protestors will demand it happens now! The current volatility of energy pricing demonstrates a massive underlying transition problem and political naivety. We can’t fundamentally change energy provision overnight.

Climate protestors are furious this generation has “stolen” their futures will be even less happy if they succeed in reversing economic growth. The result will be to ensure billions of children as yet unborn don’t just face rising temperatures and sea levels, but also chronic poverty, unemployment, starvation, migration and rising conflict over the environment – water being the primary threat.

The real failure of governments wasn’t ignoring Greta et al and the evidence of global warming, but not anticipating the need for an energy transition plan. In coming years, the noise between climate protests and the slow pace of the transition to clean energy will get louder and become ever more likely to dislocate politics. It sets up a political crisis within the next few years as empowered green campaigners garner more airtime. This has massive market implications.